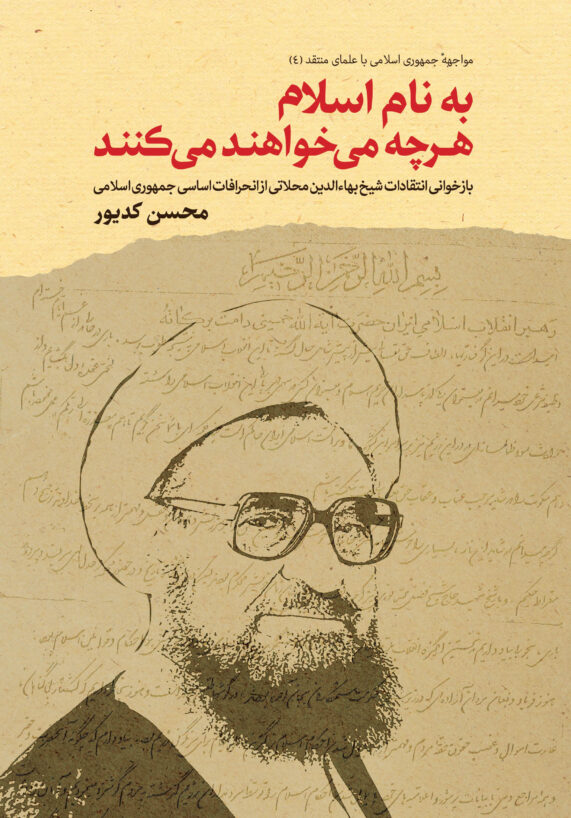

The Dissident Ayatollah of the Islamic Republic of Iran series (4)

Arbitrary Rule in the Name of Islam

Revisiting Ayatollah Maḥallātī’s Fundamental Critique of Theocratic Iran

Majmu’eye movajeheye Jomhouri Eslami ba ‘Ulamaye Muntaqid (4)

Be nam-e Eslam har cheh mi-khahand mi-konnad

Baz-khani-e enteqādāt-e Shaykh Bahā’ ad-Dīn-e Maḥallātī as enherāfāt-e asāsi-e jomhuri-e Eslāmi

Mohsen Kadivar (1959- )

First Edition (as series of articles): August-December 2016

Second Edition (as web-book): January 2018

322 pages

Official Website of Mohsen Kadivar

English Preface

Preface

The preface is divided into five subsections: “Source of emulation” (marja‘) with foresight in Fars province, a private letter to Khomeini and his response, the final pronouncement: declaration of fundamental perversions in the Islamic Republic, the necessity of revisiting the past critiques vis-à-vis the Islamic Republic, and a few points about the book.

- “Source of emulation” (marja‘) with foresight in Fars province

Three senior combatant jurists (mujtahidūn) stood up in the uprising of 5 June 1963 against Shah’s dictatorship: Sayyid Khomeini (d. 1989) the founder of Islamic Republic fifteen years later, Sayyid Ḥassan Ṭabāṭabā’ī Qummī (d. 2007) and Shaykh Bahā’ ad-Dīn Maḥallātī (d. 1981). The latter two also protested against the Islamic Republic in its early post-revolution phase: At the start of 1981, Sayyid Qummī was placed under house arrest illegally by his previous ally, Khomeini. His confinement did not change even after Khomeini’s death. Shaykh Maḥallātī wrote two letters of protest to Khomeini in June and September of 1980, and in January 1981 issued a pronouncement questioning the legitimacy of the Islamic Republic.

Maḥallātī, a student of Mīrzā Nā’īnī, Sayyid Abū al-Ḥasan Iṣfahānī, Ḍiyā’ al-Dīn ‘Arāqī, and Shaykh Muḥammad Kazim Shīrāzī in Najaf, earned a certificate of ijtihad from the last two scholars. In 1930 he began teaching advanced classes (dars-e khārij) to most of the scholars from Fars province at the Muqīmiyyeh seminary in Shiraz. His commentary on Ayatollah Boroujerdi’s (d. 1961) Practical Manual (Risāleh-ye ‘Amaliyyeh) was published in 1961 and his own in 1970, after the death of Ayatollah Ḥakīm (d. 1970). Many of the inhabitants of the province and southern Iran were Maḥallātī’s followers (muqallid).

Maḥallātī was an insightful, discerning, and a combative jurist. He accompanied his father and 700 fighters from Shiraz to Borazjan in 1915 to help the opposition movement against the British imperialists in Tangestan. During his 1949 pilgrimage to Makkah he discussed the importance of Muslim unity with Sunni scholars, one of whom was Hasan al-Banna, the founder and leader of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood (who was assassinated by the Egyptian secret police that same year). He supported Muhammad Musaddeq’s (d. 1967) attempted nationalization of the petroleum industry in 1950s, and had close relations with professors and high school teachers. His weekly lecture series on the fundamentals of creed at the Mawlā mosque were compiled in a work entitled Rāhnemā-ye Ḥaqq. One of the evidences of his independent scholarship in the area of jurisprudence is found in Resāleh-ye Naqḍ-e Ḥukm-e Ḥākim (Reversal of Ruler’s Sentence) in which he critiques Mīrzā Ᾱghā Iṣṭahbānātī (aka Sayyid Ibrāhīm Ḥusaynī Iṣṭahbānātī), senior jurist residing in Najaf, on Fakhr al-Muḥaqqiqīn’ case in 1958.

During September 1962, he began expressing his opposition to the enactment of the “Provincial and District Councils Bill” (anjumanhā-ye eyālatī va velāyatī). Three persons were in the forefront of opposing Muhammad Reza Shah’s White Revolution and the movement of 5 June 1963: Sayyid Ruhullah Mussawi Khomeini in Qom, Sayyid Ḥassan Ṭabāṭabā’ī Qummī in Mashhad and Shaykh Bahā’ ad-Dīn Maḥallātī in Shiraz. In the letters written to the Shah by the most senior jurists (i.e., Mīlānī, Shariatmadari, Gholpaygānī, Mar‘ashī Najafī, Ḥakīm, Khū’ī, Khwānsārī, Shāhroudī, Behbehānī, Ᾱmulī, and Ᾱshtiyānī) appealing to him to free the imprisoned scholars, three names appear consistently: Khomeini, Maḥallātī, and Qummī. After four months of imprisonment, Maḥallātī returned to his hometown of Shiraz to an enthusiastic welcome in September 1963. From there, he continued his opposition. In June 1964 he wrote a letter to the military tribunal asking that several political prisoners be freed, namely, Sayyid Maḥmūd Tāleghānī, Mehdi Bazargan, and Yadollah Saḥḥābī. In addition, he explicitly supported Khomeini’s requests, made after the latter’s exile to Turkey, among them Khomeini’s opposition to the Bill of Capitulation [granting immunity to American military advisors]. At the same time, Maḥallātī likened the Shah to Pharaoh.

In June 1967 during the Israeli-Palestinian war, Maḥallāti supported the Palestinians. In July and September 1971, he fiercely opposed the 2,500-anniversary celebration of the monarchy in Shiraz. In December 1971, he sent a telegram to the leader of the Iranian Senate to protest the insults hurled by two of its members against the exiled Khomeini. In January 1972, he and other scholars of Fars province signed a petition to prevent the execution of founders of the Mujahidin-e Khalq Organization (MKO). In January 1977, he advocated in favor of the oppressed Lebanese Shi’ites. He opposed the holding of a cultural festival in Shiraz sponsored by the royal family in August 1977. The analytical proclamations he issued during October 1977, when the movement against tyranny, despotism, and imperialism came to the fore again, until the climax of the revolution in 1979 are all preserved in historical archives.

Maḥallātī was counted among the senior jurists who were dissatisfied with the establishment of the Islamic Republic in the early part of 1979. He sent several notifications and reminders to Khomeini concerning revolutionary courts’ excessive nature and the newly appointed officials’ violations of Islamic law. Deeply disappointed by the excessive zeal of his hometown’s empathetic revolutionaries in admonishing the people, he left Fars province in the spring of 1979. Even though he had voted in favor of establishing an Islamic Republic, as had Shariatmadari and Qummī, all of them had objected to the election of the Assembly of Experts for writing the Constitution of Islamic Republic. After fourteen people from Shiraz were executed at the hands of Ṣādiq Khalkhālī, he wrote a stern letter to Khomeini on 16 July 1980. In September of the same year, he strongly objected, on Islamic legal grounds, to the method employed in dividing the land. Khomeini’s terse response to these letters is not recorded in the compiled collection of his statements (Saḥīfeh-ye Imām). However, Maḥallātī’s most important proclamation was issued seven months before his death in January 1981. The government organs attempted to deny its origin, but Maḥallātī affirmed its authenticity from hospital. This proclamation was in reality a politico-religious last will and testament of this protesting senior jurist.

Maḥallātī passed away honorably. Even though Khomeini glorified his compatriot in his condolence message, but didn’t hold commemorative ceremony neither in Qom nor in Tehran. Instead, Sayyid Aḥmad Khwānsārī held one. The government also prohibited the holding of a commemorative ceremony scheduled to be held at Tehran’s Arak mosque, sponsored by Sayyid Abulfadl and Sayyid Rida Musawi Mujtahid Zanjānī and Mahdī Ḥā’irī Yazdī.

- A private letter to Khomeini and his response

Maḥallātī’s protest letter to Khomeini and the latter’s response are among the most important evidences of the Islamic Republic’s conduct during its first decade of existence. The execution of Shirazis on 3 July 1980 is but one small example of its misconduct. Officials of the Islamic Republic dismissed the global judicial system as vestiges of the West and thus set up revolutionary courts, believing this to be more in keeping with Islamic law. The judges were selected from the clerical class, and the procedures and ordinances were implemented by the Islamic Revolution Council. Khomeini appointed the first chief judge, Ṣādiq Khalkhālī, who used to write his judicial rulings by himself. A few days after the revolution’s triumph, Khalkhālī began the proceedings at the Refāh School, which was Khomeini’s temporary residence too. When Khalkhālī was elected to the Parliament (Majlis) as the representative from Qom after a year and some months, his scope of activity was curtailed and he was placed in charge of prosecuting cases dealing with drug trafficking only.

In general, the judgments issued by Shiraz’s revolutionary courts between the winter of 1979 and the spring of 1980 were relatively closer to the Islamic law than was the case elsewhere. The revolutionary agencies did not take a favorable view of the judgments issued by Asadullah ‘Andalīb against those who supposedly opposed the revolution. The zealots in the Revolutionary Guards and the Office of Friday Prayer were anticipating the execution of some of the detested members of the Shah’s regime, even though they were not guilty of killing anyone. These fanatics, not content with imprisoning these people, even if it was to be for life, wanted the revolutionary courts to invoke the public welfare to justify their judgments and delegate the reins of judicial rulings to the imam of Friday prayer or the leader of Revolutionary Guards.

In 1980, two groups emerged in Shiraz at the same time: (1) those who believed that whatever they perceived to accord with the revolution also agrees with the secular and religious law and that the judges should follow the political will and (2) those who subscribed to the concept that secular and religious law ought to be the criteria for defining the public welfare and exercised caution as regards people’s life, property, and honor. Each group had the backing of an eminent hometown jurist. The various factions did their best to stigmatize each other as “anti-revolutionary.” The Friday prayer leader and the head of the Revolutionary Guards were dubbed “revolutionaries,” and the local “source of emulation” (marja‘al-taqlīd) and ḥākim shar‘ were labelled “anti-revolutionaries.” The name of Shaykh Bahā’ ad-Din (pride of religion) was distorted to Bīḥāl ad-Dīn (a person who exemplifies lethargy and dullness in religion)!

“Revolutionaries” who had honed in on Khalkhālī as their point person for getting a judgment to execute the prisoners invited him to Shiraz under the guise of adjudicating drug trafficking cases. As soon as he arrived at the Revolutionary Guards’ station, they presented him with a pre-arranged skit in which a number of family members, who they claimed were from the families of martyrs, petitioned Khalkhālī to mete out the same punishment (i.e., execution) to “anti-revolutionaries” as was being meted out to drug-traffickers. But the town had its own official ḥākim shar‘ (Islamic judge) and, moreover, Khalkhālī had no legal or religious mandate outside the area of drug-trafficking cases. The ḥākim shar‘ and Shiraz’s prosecuting attorney were not prepared to provide him with the prisoners’ dossiers. The latter, at the apex of arrogance and disdain and without any access to their dossiers, brought the prisoners from ‘Ᾱdilābād jail to the Revolutionary Guard’s station with the latter’s help. Within five hours he adjudicated twenty-four cases, out of which fourteen were sentenced to death and executed right there. This caused Shiraz’s “revolutionaries” great happiness and satisfaction.

According to official court records, the fourteen people who were executed had had their case adjudicated by Shiraz’s ḥākim shar‘on 9 July 1980 – four were sentenced to imprisonment and were serving their sentences. Shortly thereafter, two of them had their cases commuted and were pardoned. They were awaiting their release when they were executed! One of these was an Jewish woman who had no previous criminal record or conviction. Despite being arrested only one hour earlier, a few hours later she was executed. The local courts were still examining the dossiers of the nine other persons who were executed.

Members of her family filed a grievance with Maḥallātī, Shiraz’s “source of emulation,” outlining the injustice and pointing out that not only she had been the mother of four children, but she had also been three months pregnant. They also asked him to revoke the judgment on seizing her property. Profoundly affected upon hearing of this incident, Ayatollah Maḥallātī wrote a stern four-page letter to Ayatollah Khomeini a week later on July 16 “With deep regret and sorrow, I must say that the outcome of delegating many of the affairs to incompetent, obsessive, and power-hungry individuals has produced a climate of hopelessness and despair vis-à-vis the Islamic Revolution. People are gripped with a sense of dread and fear.” He continued, “God is my witness that a few religious and pious persons have proposed migrating because the violations are so apparent, as is the inability to prevent their occurrence. At a minimum, one’s departure would not expose the person with information about these [horrific] incidents.”

Maḥallātī strongly condemned the “horrid massacre [on July 3] in Shiraz at the hands of a judge appointed by you” and asked: “How is it possible to justify or rationalize a person who is ḥākim shar‘ in a court with a specific portfolio (i.e., Khalkhālī) to interfere in a situation where the accused has been convicted and is serving his sentence?” Secondly, he censures the Islamic Republic:

Dear Ayatollah Khomeini, is it not our intention to export the revolution around the world and rescue the people from oppression and destruction? How? By presenting this abhorrent and hard-hearted visage of Islam that we have formed? Is it possible to spread Islam with violence and force or by logic, empathy, and justice? If we are not able to construct a unified government in which the responsibilities of each member are specified instead of the existing numerous centers of power, then where are we heading?

Sayyid ‘Abd al-Ḥusayn Dastghīb, the Friday prayer leader of Shiraz and Khomeini’s representative in the province, launched a staunch defense of Khalkhālī’s horrid actions in a telegram dated 14 July 1980 and during an interview on 9 September 1980. He zealously vouchsafed Khalkhālī’s knowledge and piety, defended the executions, and considered Judge Asadullah ‘Andalīb incompetent to handle these cases. Instead of taking Khalkhālī to task and demanding that he account for his actions, he decided to dismiss ‘Andalīb from his judicial post in Shiraz.

Seventeen days after these executions and four days after Maḥallātī’s letter, Khomeini explicitly defended Khalkhālī and the revolutionary courts in a public speech delivered in the presence of the Supreme Judicial Council and judges.

In addition to his letter of 30 July 1980, Maḥallātī expressed his objection in two other instances at the local and the national levels. With regards to the former, he said: “Some do whatever they please under the banner of Islam, and this stands out as the most critical danger for a nation’s people.” In the case of the latter, he defended ‘Andalīb: “A religious court sentences a person to life imprisonment or fifteen years and another ḥākim shar‘ hastily sentences them to execution.”

Khomeini responded to Maḥallātī’s grievances on 1 August 1980: “This revolution is grander than the best inevitable global revolutions. It is neither realistic nor reasonable to expect that everything that occurs will be in harmony with our wishes. However, efforts are being made to address the concerns, and, God-willing, they be in agreement with the luminous shar‘.” This response is not to be found in the Ṣahīfeh Imam. In actuality, Khomeini did not entertain Maḥallātī’s fundamental criticisms as valid. ‘Andalīb was not prepared to resign, vacate his post, and hand it over to the regime and, as such, was dismissed in a low-key manner without any fanfare in September 1980. This brought the Shiraz courts in line with the other revolutionary courts.

III. Final pronouncement: Declaration of fundamental perversions in the Islamic Republic

During the final days of his life, Maḥallātī, acting as a bulwark for the Shari‘ah and a defender of freedom, issued an ultimatum to the authorities. His proclamation of February 1981 was, in reality, his politico-religions last will and testament. This eminent scholar, who had spent thirty years fighting to rehabilitate the law and establish justice, freedom, and religious standards, contended that the Islamic Republic was on the wrong track and was carrying out the same oppression and despotism that had prevailed before the Revolution [in 1979] in the name of the so-called apparent Islam:

From the start of the bloody national revolution, it deviated from its true course because the power was wielded by those hankering for this world and of unknown identity in a clerical garb or otherwise. They brought forth a new Islam; dominated the most sensitive governmental organs; and issued wrong decisions in the areas of the judiciary, society, and politics. Unfortunately, the years-long drawn-out struggle, along with the people’s sacrifices, was set ablaze in the fire radiating from the greed for power and wanting to settle scores. The fear and worry are that the Islamic nation of Iran may suffer annihilation. The ghastly danger that is palpably felt is as follows: The blood-thirsty Pahlavi regime, which suppressed human rights and committed crimes that filled many pages of history, was not done under the banner of Islam because everything was attributed to the executioner Shah, who was authoritarian and a lackey of the West. However today, under the banner of Islamic government, as well as [Imam] “Ali’s model government” and the claims of freedom and non-affiliation, we are witnessing the repetition of the same painful circumstances and oppression of the past.

Toward the end of his life, Maḥallātī issued a decree that charged the so-called Islamic Republic with lacking religious legitimacy and characterized it as tarnishing Islam’s image and acting against the Prophet’s norms:

As one who desires to safeguard the pure Shari‘ah promulgated by the Prophet and to defend freedom, I sense an acute threat and danger from that which has befallen [our] beloved Islam and the Islamic nation. I implore the collective dignified countrymen who are independent and devoted to their religion to closely monitor and scrutinize the government and to organize themselves and be united, more than ever before, so that they may have control over their own fate.

His harsh and pointed criticism is directed at the judiciary, the revolutionary courts, incompetent religious judges, executions, torture in the name of implementing the discretionary punishments (ta‘zīr), the embezzlement of funds, arbitrary imprisonment, the absence of job security, the ascendancy of the ignorant and pressuring the scholars and universities, closing down the university under the guise of cultural revolution, extreme censorship, hero worship, no plan for economic growth, halting factory production, sycophancy, and an ostentatious display of piety that requires abusing certain aspects of religion:

That which has been allowed to befall the honorable nation and patient Iranians is not only against the Islam that Muhammad promulgated, but is also the cause of disfiguring and demeaning the Islamic Revolution of Iran. A very abhorrent visage of Islam, which is the religion of character building and love and compassion, knowledge and logic, is portrayed such that the world considers this compassionate religion to be regressive, anti-knowledge, and in favor of violence! With a heavy heart and deep grief, what calamity is befalling on the image of Islam?

In actuality, Maḥallātī leveled his objections against all senior and prominent government official involved with economics, culture, and domestic and foreign policy. Khomeini summarily dismissed these repeated written and oral entreaties on the grounds that they were natural occurrences in any revolution although, according to him, the government was on a corrective course to rectify the errors. Maḥallātī failed to receive a convincing response and thus opted to separate, before his death, his tenure of struggle from that of the Islamic Republic. And indeed, that is exactly what he did.

- Necessity of revisiting the past critiques vis-à-vis the Islamic Republic

Maḥallātī is not the first senior jurist to object to the conduct of the revolutionary courts’ officials. Prior to him Sayyid Ḥasan Ṭabāṭabā’ī Qummī, one of the three leading figures who had participated in the June 1963 uprising, had severely scolded the functions of revolutionary courts from a traditional Islamic perspective. However, the charm and importance of his letter lies in its evidentiary nature of the existing circumstances on the one hand and an expression of his integrity, justness, and foresight on the other. In addition to Maḥallātī and Qummī, AbūalFaḍl Mūsawī Mujtahid Zanjānī wrote a letter in which he raised serious objections to the revolutionary courts’ conduct and targeted the revolution’s deviant foundations.[1] This letter was circulated two months after Maḥallātī’s letter.

At that time, however, no critical letters or proclamations could be published in a newspaper or a magazine. What can be said of a revolution and an Islamic regime that bars acknowledged eminent and empathetic jurists with a record of struggling for justice, aspiring for independence and freedom, who are pious and insightful such as Maḥallātī and Zanjānī from circulating their criticisms? If these critical letters had been circulated, then we would never have found ourselves in the dismal position of witnessing the same violations and transgressions forty years later.

All of the three persons cited above were more illustrious in their confrontations against injustice and had precedence in this enterprise than Khomeini. Branding these luminaries as lacking in political insight, aspiring to protect their own vested interests, or stooges of foreigners would not stick. Maḥallātī’s letter and pronouncement are still fresh even after thirty-seven years. Is the situation of most of the judges, Friday prayer leaders, and heads of the Revolutionary Guards any different today than it was thirty-seven years ago?! Are not the ḥukkām shar‘ and revolutionary courts still playthings in the hands of the politicians?

The aim of studying these criticisms is not to merely uncover the past. Rather, these letters encapsulate the pain and suffering of a nation that is ablaze because of the rulers’ naïveté and injustice. The insightful senior and eminent scholars who were aware from the very start of the Islamic Republic’s fundamental digression attempted to convey their objections with civility; however, the rulers prevented their circulation among the larger public and instead falsely propagated that their regime had been approved and authenticated by all of the “sources of emulation” and jurists (Shi’i authorities). Now, the declaration of one of the most senior Shi’i authorities unfolds the conspiracy of the liars.

Even though I was born in Fars province and spent my youthful life in Shiraz (1964-81), I was unaware of Maḥallātī’s letters and proclamation as well as Khomeini’s response until 2012. During part of my youthful years of excitement and vibrancy (January 1979 to June 1981), I was an advocate of the revolution in the form of being an energetic and active member of the University of Shiraz’s Muslim Student Association and close to the city’s Revolutionary Clergy (Rūḥāniyyat-e Enghelābī) as well, which represents the very same groups that Maḥallātī criticized so harshly in his letter. In September 1980 (after the closure of universities in May 1980), I decided to continue my seminary studies under the guidance of Sayyid ‘Alī Muḥammad and Sayyid ‘Alī Asghar Dastghīb in order to both enhance and reform my cultural awareness. After my departure to Qum in the summer of 1981, I was preoccupied with settling down in the new city and the seminary and thus, fortunately and per chance, able to distance myself from the harsh and overzealous politics of the day. In any event, I was part of the revolutionary crowd (siyāhī-ye lashkar) that Shaykh Maḥallātī justifiably criticized in his letter of June 1980.

I must state with forthrightness that both my generation and I are indeed deserving of blame and reproach for playing a minor accessory role to the extent of being part of the revolutionary crowd. I was unaware of Maḥallātī’s worth and the value of his composed and steady views during his lifetime. Belatedly, a few decades later I extend my respect and reverence to those who discerned much earlier than many, due to their experience, and expressed their fierce objection when they realized that the revolutionary regime was deviating from the ideals, sacrificing religion for political gains, becoming oppressive and duplicitous, and violating secular and religious norms. Now, my effort is focused on analyzing the legacy of knowledge of those who had precedence in foresight, piety, and progress so that I can critically scrutinize previous generations and thereby offer lessons and counsel for the present and future generations. Clearly, our predecessors are not beyond reproach and will be critiqued when warranted. I have made every effort to be fair and objective as well as to examine the historical event in its own context. The verdict on my success in this regard is up to the reader. I welcome your criticisms and suggestions for improvement. Some of the sources in this work have been made available for the first time.

This research is based on sources that were gathered over a course of a number of years and with great effort. As some of the individuals mentioned obviously have their own perspective and perhaps additional sources upon which they rely, they may disagree with my analysis. I have attempted to narrate historical events without any interpolations. If any new sources and documentation that would alter my conclusions are introduced, then I will gladly and enthusiastically make the necessary correction to enhance my research, for I have no vested interest in subscribing to any particular view.

This work is not designed to elevate, demean, or belittle anyone. However, I am harsh in dealing with those who exhibit no respect for others’ lives and transgress the ethical, secular, and religious guidelines. We will also come to know and esteem those figures who, in the midst of being surrounded by revolutionary fervor, gave preference to humanism, religious values, ethics and law, and remained unafraid of censure by those who reproached them. The merit of this work far transcends disputation, jealousy, and rivalry or devaluing and demeaning any locality, guild, or faction.

I make no claim to being a historian, and the historical incidents narrated in this work are coincidental and necessary. My primary motive is to understand the phenomenon of “Islamic Republic,” which has had a major impact upon me and my generation. The Islamic Republic’s history is intertwined with that of Shi‘ism and Islam. I have strived to understand the evolution of contemporary Iranian political thought, especially of those who are on the front lines of preserving religion. My primary concerns are: What is the opinion of the first-tier Shi‘i scholars regarding the Islamic Republic and the notion of “governance of the jurist” (wilāyat-e faqīh)? Were the Iranian “sources of emulation,” mujtahids, and jurists silent in the face of the gruesome conduct of the revolutionary courts, executions, embezzlement, and all that was presented under the banner of Islam? Did they propagate and affirm Khomeini’s ideas and act as his followers? Were the first-tier scholars and “sources of emulation” who were critical of the Islamic Republic and of Khomeini’s worldview in the minority or the majority?

The clear unrest and turmoil in the seminaries and the department of humanities at universities, especially the theology department, is due to not paying attention to critical reflection, historical method, and clear-cut evidence. In my opinion, if these three aspects had been heeded many of our assumptions, authentication, and perceptions of the world in which we live would have become more nuanced and sophisticated. The evolution of theology, jurisprudence, Qur’anic exegesis, and Hadith science under the rubric of Islamic studies is intimately connected with these three factors. The benefit I acquired from undertaking historical research has been an impetus to providing a fresh perspective in my own field of expertise. I do not regard engaging in critical historical inquiry to be a waste of time, nor do I reject our predecessors’ methods. Quite the contrary, I view doing so as enriching our tradition with the use of modern methods.

V .A few points about the book

This book is part of a larger research project on Shaykh Bahā’ ad-Dīn Maḥallātī’s views and positions. In essence, it is an analysis of the criticisms he made in his letter and proclamation, along with some brief points on the politics surrounding the ceremony to commemorate his death, namely, some of the events that took place during the last fifteen months of his life.

The title is derived from his media interview on 30 July 1980: “Some do whatever they please under the name of Islam, and this stands out as the most critical danger for a nation’s people” – in other words, total absolutism in administering the state under the banner of Islam. His proclamation of 9 February 1981, which constitutes a religio-political last will and testament, conveys the same reality but in different words:

The ghastly danger that is palpably felt is as follows: The blood-thirsty Pahlavi regime, which suppressed human rights and committed crimes that filled many pages of history, was not done under the banner of Islam because everything was attributed to the executioner Shah, who was authoritarian and a lackey of the West. However today, under the banner of Islamic Government, as well as [Imam] “Ali’s model government” and the claims of freedom and non-affiliation, we are witnessing the repetition of the same painful circumstances and oppression of the past.

That is, Maḥallātī complains that the despotism and oppression being done in the name of Islam and the pain he is experiencing is due to Islam’s disfigurement.

That which has been allowed to befall the honorable nation and patient Iranians is not only against the Islam that Muhammad promulgated, but is also the cause of disfiguring and demeaning the Islamic Revolution of Iran. A very abhorrent visage of Islam, which is the religion of character building and love and compassion, knowledge and logic, is portrayed such that the world considers this compassionate religion to be regressive, anti-knowledge, and in favor of violence! With a heavy heart and deep grief, what calamity is befalling on the image of Islam?

Likewise, the subtitle of this book, “Revisiting Ayatollah Maḥallātī’s Critique of Fundamental Perversions of theocratic Iran” is also obtained from his pronouncement:

As one who desires to safeguard the pure Shari‘ah promulgated by the Prophet and to defend freedom, I sense an acute threat and danger from that which has befallen beloved Islam and the Islamic nation. I implore the collective dignified countrymen who are independent and devoted to their religion to closely monitor and scrutinize the government and to organize themselves and be united, more than ever before, to have control over their own fate; to follow-up on the implementation of the true and noble Islam; and to save our nation from the danger of deviance and, God-forbid, collapse.

His warning “danger of deviance” refers to perversions and distortions in the area of ethics and religious governance in the name of Islam. In such a situation, the phrase “Islamic Republic” is meaningless and hollow.

It is my great pleasure to thank those who have played an instrumental role throughout my research. Foremost among them is Dr. Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Maḥallātī, son of the late Shaykh Bahā’ ad-Dīn Maḥallātī and professor emeritus in geography at Shahīd Beheshtī University. This work would not have seen the light of day without his unparalleled assistance in gaining access to sources and documentation that were unique and only in his possession. In addition, he patiently provided valuable help by responding to my many queries. This work is the fourth one in the “The Dissident Ayatollahs and the Islamic Republic of Iran” series. [2] Hopefully, I will have the ability and the good fortune to publish additional volumes under this series.

As there is no hope of publishing this work in book form in Iran, I have opted to publish it on my website. Contrary to Iranian law, from 2009 onward I have been barred from publishing anything – books, articles, and interviews. The claim made by officials of the Islamic Republic in political and cultural sectors that no writers have been censored and prohibited from writing is a flagrant lie and absurd, unless they do no regard me as a writer! As those who publish online receive no royalties, this is part of a hefty price, in the form of spiritual and material loss, one has to pay for daring to criticize the administration of the “sacred Islamic Republic.” I have not yet decided whether to publish this monograph in book form in other Persian-speaking countries or Persian presses in Europe or America. However, my primary audience is Iranians residing in Iran and, as such, my countrymen will be able to access this work free of charge and without any hindrance. I continue to look forward to a day when I can once again enjoy the happiness and bliss of publishing a monograph in my own country.

Mohsen Kadivar

January 2018

[1]. Enḥerāf-e Enghelāb: E‘lāmiyyeh 12 Shariīvar 1359 Sayyid Abul-Fadl Musawi Mujtahid Zanjani, (Hijacking of Iran’s Iranian Revolution: The 9/3/1980 Declaration of S. A. Musawi M. Zanjani), Edited with notes and introduction by Mohsen Kadivar, , July 2016, 157 page.

[2]. The three previous works in this series are: Evidence of Dishonoring the Revolution: Examining the last years of Ayatollah S. Kazim Shari’atmadari’s life (Asnadi az Shekaste Shodan-e Namous-e Enqelab:Neghahi be Salhaye Payani-e Zendeghani-e Ayatollah Seyyed Kazim Shari’atmadari)(2012, 2nd edition: 2015, 447 pages); The Rise and Fall of Azari Qomi: The Evolution of Ayatollah Ahmad Azari Qomi’s Thought 1923-1999 (Faraz wa forud-e Azari Qomi: Seiri dar tahawwol-e mabaniy-e afkar-e Ayatollah Ahmad Azari Qomi 1302-1377 (2014, 488 pages); Testing the Revolution and the Regime with Ethical Criticisms: Ayatollah Seyyed Mohammad Rouhani, Slander, and Marja’iyat (Enqelab va Nezam dar buteye Naqd-e Akhlaqi: Ayatollah Seyyed Mohammad Rouhani, Mubaheteh va Marji’iyyat) (2013, second edition: 2015, 223 pages).